views

It is widely believed that Spielberg's ability to capture the wonder and terror of childhood is a result of how his own experiences have continued to weigh on his heart and mind more than fifty years later. By this point, all of that baggage has become inextricably entwined with the mythology of Hollywood's most adored hitmaker.

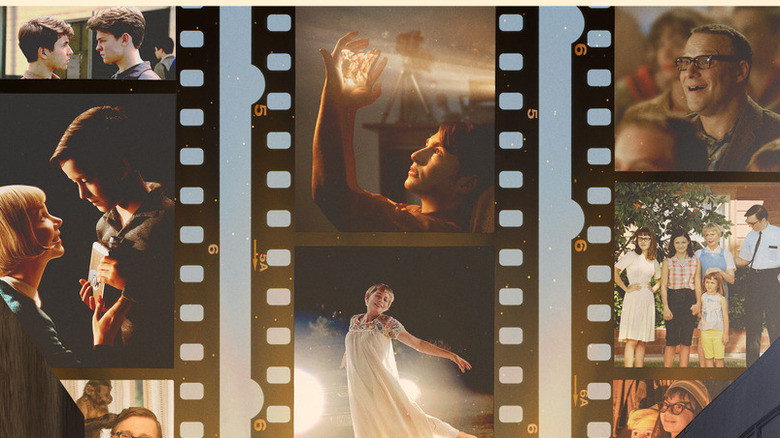

Spielberg eliminates everything but the most minimal vestige of fabricated separation between his work and their experiences with his newest coming-of-age film, The Fabelmans. The film is very lightly fictionalized and tells the story of an idealistic child from a Jewish family growing up in the American Southwest and falling in love with movies as his parents fall out of love with one another. See some online shopping reviews here. Tony Kushner, the great playwright who has written some of the director's recent forays into American history (including last year's brilliant West Side Story), co-wrote the script for the movie. Every scene in the movie seems to have been taken straight out of Spielberg's childhood nickelodeon. The big-screen memoir is presented as a sparkling-tragic spectacle of a healing exorcism.

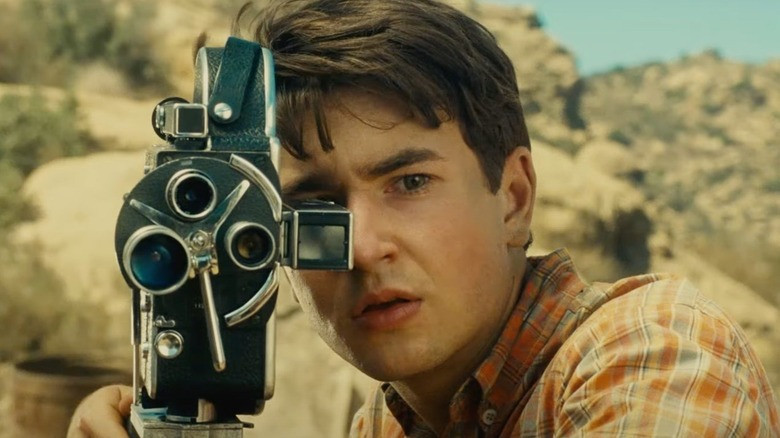

The Fabelmans, a dramatization of the filmmaker's adolescence that spans from the early 1950s to the late 1960s, naturally starts with what might be his earliest memory of seeing a movie, a formative viewing of The Greatest Show on Earth. Young Sammy (Mateo Zoryon Francis-DeFord), terrified by the visuals of a train severely derailing in the movie, eventually recreates the action with his own model locomotive, damaging it to get rid of his lingering dread. His mother, a former pianist named Mitzi (Michelle Williams), explains to his father, a computer expert named Burt (The Batman's Paul Dano), that "He's attempting to get some sort of control over it," which may just about sum up the aims of The Fabelmans itself.

Spielberg will follow Sammy and the rest of the Fabelmans family, including the boy's two younger sisters, across more than a decade of domestic strife from New Jersey to the suburbs of Phoenix to California. Two regularly overlapping tracks are switched between in the drama. Sammy slowly grows into a budding filmmaker as we watch, picking up tips and tactics through increasingly complex home movies (including a Western and the legendary 40-minute war movie of his youth, Escape from Nowhere). The child observes from the sidelines as his parents drift away at the same time. Burt's coworker and close family friend Bennie (Seth Rogen), whose relationship with Mitzi is clearly more than just platonic, is a third figure in their marriage and the source of a lot of their conflict.

Spielberg spends a lot of time on details that are too exact to be made up in The Fabelmans, which appears to be based on real events. Moments out of time, captured in the glow of Janusz Kaminski's customarily heavenly cinematography, include the crinkle of a paper tablecloth, the gentle pulse on the neck of Sammy's dying grandmother, and the tough-love wisdom of Sammy's uncle (Judd Hirsch, nearly stealing the movie in one fantastic scene). The storyline has an episodic feel to it. Kushner and Spielberg thread together moments of everyday life from the middle of the 20th century to create a drama that is alternately heartbreaking and sentimental. The Fabelmans eventually transition into Sammy's high school years, when he must deal with anti-Semitism in 1960s California while pursuing a beautiful Catholic classmate. Sammy is now played by Gabriel LaBelle, in a wonderful breakthrough performance (Chloe East).

Despite the energy he has added to Spielberg's work over the previous several years, Kushner is unable to hide the therapeutic undertones of this film, which occasionally bleed into the dialogue and certain pivotal scenes. The characters frequently seem to be expressing the fundamental truths of Spielberg's life, or perhaps the things he wishes they had uttered at the time to make sense of everything earlier. Is this how he actually remembers those events or is his shrewd mainstream storyteller side taking over and emphasizing his major ideas for the front row? The opening scene of The Fabelmans is possibly its most overtly thematic moment, in which Burt explains to his little son the concept of persistence of vision while Mitzi merely informs him that "movies are dreams." Sammy (and, thus, Spielberg) are supposed to be understood as the offspring of both grownups. He was pragmatic, and she had a sense of magic, and together they made the crowd-pleasing director of legend.

Although The Fabelmans is sweet, it's hardly the epic heartbreaker you would hope for or anticipate. It sometimes has a similar immersive quality to a snow globe. Like the insect preserved in amber in Jurassic Park, Spielberg has covered his memories in such a thick layer of veneration that we can only gaze in awe from a distance rather than enter them. Ironically, becoming closer to these actual events may have actually made us feel less close to them. Even while The Fabelmans is undoubtedly Spielberg's most intimate film—his story is barely embellished—it doesn't fully immerse us in his feelings like the less literal E.T. did.

However, the movie matures alongside Sammy, often growing more complex and vulnerable as it goes on. When focusing on the relationship between Spielberg's parents, it is at its most effective and unsettling. Williams and Dano provide us (and perhaps the filmmaker) an imprintable examination of parental contrast that enables us to comprehend the gaps in compatibility that develop between their characters. These images strike a striking balance between two opposing points of view, conveying both the boy's unfiltered adolescent reaction to his parents' imminent divorce and the knowledge that can only come from hindsight. In a pretty amazing scene, Sammy examines a video from a previous camping trip and analyses the emotional swings of the people in the frames to determine what is occurring between his mother and Bennie. The realization that movies may communicate the truth—and occasionally tell you more than you want to know—is both a personal and creative one.

By the conclusion, when Spielberg gives in to the familiar urge to uplift spirits and builds to a reunion with a boyhood idol (a really humorous cameo that does feel a little like it belongs to a different movie), The Fabelmans has assumed the romantic proportions of an origin story: Finally, we learn what made the director of films like Jaws, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and a number of other cultural touchstones. One man's personal artistic epiphany transformed into a multiplex tearjerker, as bright but diffuse as the light presenting it to us—but what lingers is the impression that the tangled emotions of an upbringing have been flattened into another hymn to the power of movies.

On November 11, The Fabelmans premieres in a few theatres. All this week, we will be covering the Toronto International Film Festival. Visit A.A. Dowd's Author page to read more of his writing.